What is Nystagmus?

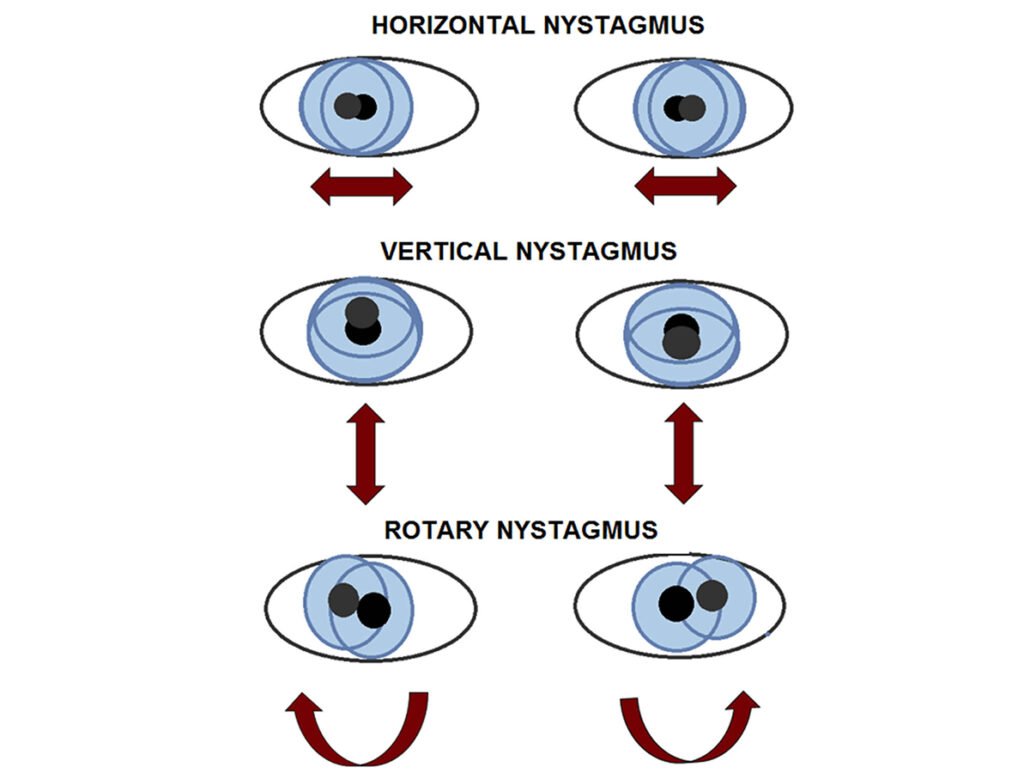

Nystagmus describes rapid and uncontrolled eye movement, if you have nystagmus your eyes will move or ‘wobble’ constantly. This uncontrolled movement can be in an up and down, circular, or side to side motion – or a combination of all. Many people with nystagmus have reduced vision due to this wobbling.

Why nystagmus happens

Nystagmus happens due to a malfunctioning of the part of the brain or inner ear that regulates this eye movement. The labyrinth is the outer wall of the inner ear that helps you sense movement and position – it also helps control eye movements.

There are 2 main types of nystagmus:

- Infantile/congenital nystagmus which appears in the first few months of life. This is usually diagnosed in young children during the first few months after they are born, and is usually caused by a problem with the eyes themselves or with the parts of the brain which control these eye movements.

- Acquired nystagmus which usually develops later in life, and is usually a sign of another underlying condition such as stroke, a brain tumour, multiple sclerosis, head injury, or a drug side-effect.

Nystagmus Symptoms

- sensitivity to light.

- dizziness.

- difficulty seeing in the dark.

- vision problems.

- holding the head in a turned or tilted position.

- the feeling that the world is shaking.

Living with nystagmus in childhood, Molly’s story (video courtesy of RNIB website)

How is Nystagmus Diagnosed?

If you think your child may have symptoms of nystagmus it is highly recommended that you see an optometrist or an opthamologist. They will look at the inside of the eye and conduct vision tests whilst also looking for other potential eye problems.

Other tests include:

- Neurological exam

- Brain MRI

- Brain CT scan

- Recording the eye movements

- Ear exam

One of the most common tests is that the doctor will ask the individual with suspected nystagmus to spin around in the chair for around 30 seconds, stop, and then try to stare at an object. If the individual has nystagmus then their eyes will slowly move in one direction and then they’ll move quickly in the other direction.

Strategies and Tips for Managing Nystagmus

- The effects of nystagmus can improve when your head is held in a particular position, which can help you to see things better. This is known as the “null zone”. This is often the direction of your gaze where your eye movements are slowest and most stable. Children with infantile nystagmus often find their null zone naturally.

- Having nystagmus means that you need longer to see or read things, so try to allow them extra time for looking at objects or reading things. Also allow them to hold books close to their eyes with their head tilted.

- Use large-print books and turn up the print size on any electronics the individual with nystagmus uses.

- Wearing hats or tinted glasses – even indoors – can help reduce glare.

- Encourage them to use their eyes by giving children brightly coloured and textured toys.

Treatment Options

- Glasses and contact lenses can help aid their vision. They cannot correct the nystagmus but can correct any refractive errors they may have and aid in vision development.

- Surgery can be used to change the position of the muscles that move the eye and then reduce the uncontrollable movements. However it cannot fully correct the nystagmus.

- Some medications can ease symptoms and may include the anti-seizure medicine gabapentin (Neurontin), the muscle relaxant baclofen (Lioresal), and onabotulinumtoxina (Botox). Injections of botox into the muscles around the eye has been shown to temporarily reduce nystagmus in some patients.

Resources

The Nystagmus Network is a UK-based charity which supports individuals affected by nystagmus and aids in the effort to finding a treatment for the condition: http://nystagmusnetwork.org/

About the Author

Liam went from being able to read and write in perfect 20/20 vision, completing his GCSE examinations in 2017, to having someone else read his results a mere few months later, on results day. He suffers from Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON), which is the acute or subacute loss of central vision predominantly affecting young adult males. There is no pain.

Liam’s Story…

I am 19 years old and still adapting to my central vision loss, writing this blog is a reminder of my adaptations over abnormality. As you read this, attempt to do so with both thumbs up in front of the centre of your eyes…. difficult right? This is reminiscent of my experience of having central vision loss.

Despite having the experience of dealing with sight loss it has taught me the fundamental coping method of having a disability. It’s the ability to adapt. Over time, and with persistence, that experience simply becomes normal. As I write this my screen is zoomed in four times. I have learned to touch type and use technology such as ‘text to speech’ that enables me to write this blog . As quickly as I lost my vision, I found I had to quickly to adapt to these changes.

With all forms of life-altering events, it does present some form of psychological torment. But in my experience, my mother felt the hardship of loss more than I did. I was caught up in adapting to my disability and spared little time thinking about the emotional consequences of the situation.

My family had a sense of hurt due to not being able to have control of the situation. I suppose nothing is harder than always being the figure who can solve problems for your child, to not being able to solve this problem. Fully understanding the problem can help with solving the emotional aspects of a disability. My adaptations ‘normalised’ my newfound disability. A combination of professional advice, along with my experience and adaptations, helped my family gain understanding and a real sense of reassurance that everything was going to be okay.

Detached Retina

Detached Retina