We are all awaiting the government’s next steps on special education and are keen to understand what future changes may come. While the system may shift in the coming years, the core purpose of the Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) is unlikely to change dramatically, as any change would require legal amendments. Until any reforms are announced, this is how the process currently works, and I will continue to monitor developments to ensure this information remains relevant.

The Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) has been widely discussed throughout the decade since its introduction. While the system has clear weaknesses, children and young people with SEND require a legally binding document that brings together the support they need to learn, communicate and participate. An EHCP is shaped by several contributors: families who share their lived experience and history, educational and therapeutic professionals who assess and advise, and the Local Authority, which ultimately decides whether an EHCP is required.

As stated in the SEND Code of Practice (CoP 9.3), an EHCP must set out the outcomes sought for the child or young person and the special educational, health and social care provision required to meet those needs. Plans should build on a child’s past experience, raise aspirations for them and outline both short and long-term goals so there is a clear path for progression.

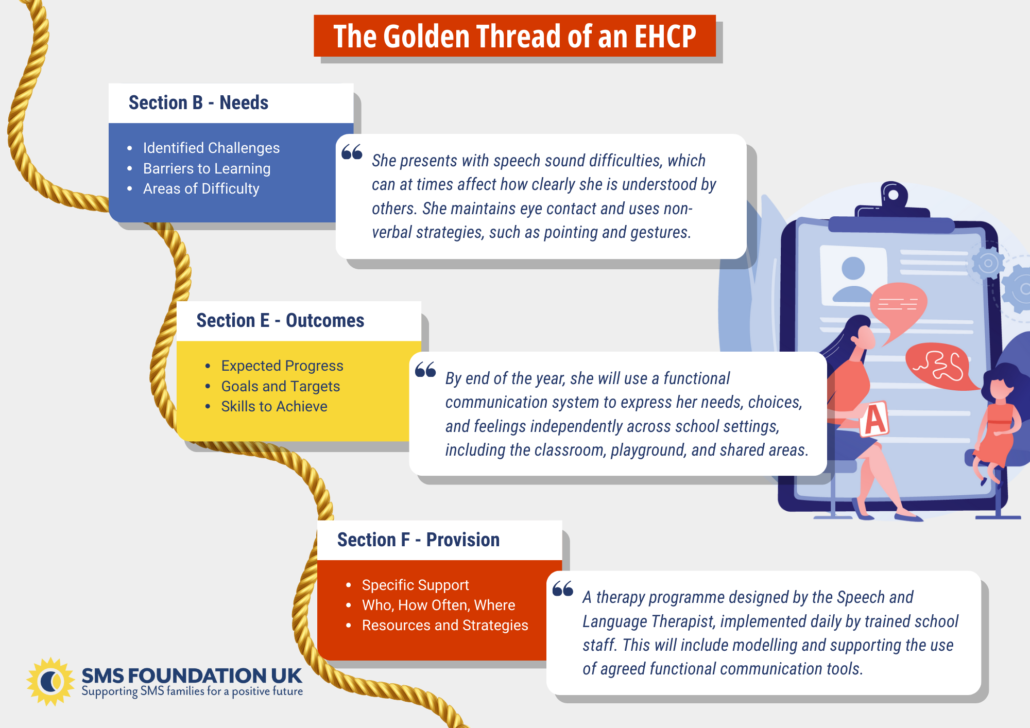

Three sections form the core of the plan:

• Section B – Need: a clear, evidence-based description of the child’s special educational needs.

• Section E – Outcomes: the measurable changes expected over time.

• Section F – Provision: the specific support required to achieve those outcomes.

When Sections B and F are written accurately and logically, outcomes become clearer, and the potential for disagreements reduce as the plan becomes more meaningful for the child. As the CoP emphasises (9.2), the purpose of an EHCP is “to secure the best possible outcomes across education, health and social care and prepare young people for adulthood.”

A well-written EHCP allows any professional working with the child, now or in the future, to understand their needs and deliver consistent support so they can thrive.

Section B – Needs

Section B is about accurately identifying and describing the child’s needs. It must offer parents clarity about what their child finds difficult while guiding professionals to ensure the document remains specific, evidence-based and updated as the child progresses. Strengths are also included in this section and frame an understanding of the child’s areas of skill.

The Code of Practice outlines four broad areas of need when fundamentally reviewing education (CoP 6.27):

- Communication and interaction

- Cognition and learning; social

- Emotional and mental health

- Sensory and/or physical needs

These headings help us understand the child’s profile and the areas in which support must be planned.

Section B is diagnostic in nature, but it is not meant to list every diagnosis a child has received. Instead, it focuses on describing the child’s needs and the barriers that affect their ability to access learning and take part in everyday school life. Even where a child is in an appropriate school placement, an EHCP is still needed to set out the support required to help them reach their full potential.

Not every area has to be included. For example, if a child does not have difficulties with academic understanding, this may not be referenced. The emphasis should remain on the areas where the child does need additional support.

The creation of an EHCP should involve the family and a wider team of professionals. While the starting point is case specific, concerns often arise when a school notices milestones are not being met or new barriers to learning emerge. Parents play a central role throughout the process, and their insight is essential. Evidence for Section B comes from a range of sources, including:

- Educational evidence: progress information, behaviour observations and strategies already attempted.

- Parental views: lived experience, concerns and aspirations.

- Medical advice: relevant diagnoses or health factors affecting learning.

- Educational Psychologist report: assessment of cognitive, learning, behaviour and emotional factors.

- SALT, OT, CAMHS etc: specialist assessments identifying communication, sensory, motor or emotional needs.

Section B must be factual, specific and concise. Well-written EHCP’s avoid vague descriptions. For example, “has difficulties with speaking” tells us very little, whereas “His developmental delay affects his speech and language skills” allows clearer understanding and planning. This need would then be reflected in Section E through a targeted outcome, with the specific provision to support phonics learning set out in Section F, such as support delivered by staff trained in phonics.

Ensuring we maximise detail strengthens Section B. For instance:

“He presents with some speech sound difficulties, which can sometimes affect how clearly he is understood. He is able to maintain eye contact and tends to use non-verbal strategies, such as pointing and gestures, to communicate his needs.”

This example outlines his difficulties, current skill, ability and necessary adaptations, giving a clearer picture of need.

As mentioned earlier, a well-constructed EHCP has a golden thread running from Section B (Need) to Section E (Outcomes) to Section F (Provision). If Section B is vague, outcomes become harder to write and provision becomes less effective.

During the annual review cycle, Section B should be updated. However, many plans remain unchanged for years, leading to difficulties during key transitions. In my experience as a school leader, students have been significantly disadvantaged when outdated EHCPs fail to reflect their current needs.

There are two important considerations when making changes. Parents sometimes feel hesitant to update the plan, worrying that acknowledging improvements may jeopardise existing support or school placement. However, nothing is lost by documenting progress. If previous difficulties re-emerge, support can be reinstated with evidence.

When entirely new needs arise, this is treated similarly to the initial assessment process and requires new evidence to be submitted. Updating Section B ensures the EHCP remains a live document; accurate, relevant and supportive of the child’s development.

Section E – Outcomes

Outcomes are designed to support change and development, raising the child’s aspirations and ensuring they align directly with Sections B and F by recognising both the child’s needs and the provision best suited to them. According to the Code of Practice (9.66), “An outcome can be defined as the benefit or difference made to an individual as a result of an intervention.”

Often the SMART format (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time-manageable) is useful for professionals and parents, as it provides clarity and a clear timeframe for progress. Timeframes are not always exact year on year, but longer-term targets are generally expected to be written around a yearly cycle and key stages.

Below are examples to illustrate how long and short term outcomes might be written:

Example Communication Outcomes for a Child with SMS

Long-term outcome

By July 2026, he will use a functional communication system to express his needs, choices, and feelings independently across school settings, including the classroom, playground, and shared areas.

Short-term outcomes

By the end of Term 1

- He will work directly with a Speech and Language Therapist to develop oral motor awareness and practise targeted speech sounds, using activities linked to his individual interests.

- He will be introduced to a range of functional communication methods within the classroom, using his areas of interest to support engagement and understanding.

By the end of Term 3

- He will consistently use a small set of agreed functional communication tools to make requests, express basic needs, and indicate preferences within structured classroom activities.

- He will be supported by staff to generalise these communication methods across different routines and with familiar adults.

By the end of Terms 4 and 5

- He will begin to use his functional communication system in both adult-directed and self-initiated situations.

- He will start to apply these communication skills in wider school contexts beyond the classroom, such as during structured playtimes, transitions, and group activities.

Outcomes describe what progress should look like for the individual child. They should be specific to the child’s needs and reflect the areas identified in Section B, including communication and interaction; cognition and learning; social, emotional and mental health; and sensory and/or physical needs.

Outcomes are typically discussed at annual reviews and then created or refined afterwards. When written clearly and informed by the child’s needs and progress from the previous year, they usually fit naturally into the plan. Clear outcomes reduce the likelihood of disagreements by giving everyone a shared understanding of purpose and direction.

Returning to the idea of the golden thread, the different sections of the EHCP should connect and strengthen each other, supporting the child’s progress through a coherent and joined-up approach. Regular communication and review with families and local authorities helps to ensure there are no surprises at annual reviews and provides opportunities for schools to bring all stakeholders together.

Section F – Provision

When writing this section, it can be easy to sound contradictory, so I want to be clear: if a provision details specific needs, the school or professional must work closely with the family and child to understand how to support those needs effectively. If they move away from the direct support outlined in the EHCP, professionals must be explicit about how this will enhance impact and development for the child.

Often Sections E and F are written together, and before I get back on my soapbox, every local authority having autonomy to design their own documents means each version looks slightly different. If one change could make a real difference, it would be aligning documentation nationally so that schools working across multiple authorities can work more seamlessly. Hopefully, as things continue to move online, updates will become easier and less painful than the old paper versions.

The Code of Practice (9.69) states:

“Provision must be detailed and specific and should normally be quantified, for example, in terms of the type, hours and frequency of support and level of expertise, including where this support is secured through a Personal Budget.”

As in Section B, Section F must be specific. It should include detailed, sometimes repetitive, information to give clarity about what is required: what will happen, how often, by whom, with what level of expertise, and in what setting. Sections B and F should align clearly.

Below are examples of the types of provision that might be included in an EHCP:

- Teaching approaches

- Therapy programmes (direct and indirect)

- Communication systems

- Sensory regulation strategies

- Mobility support

- Assistive technology

- Environmental adaptations

- Mentoring, pastoral support or mental health interventions

Using the examples above, provision in Section F must clearly explain how the identified communication needs (Section B) will be supported in order to achieve the agreed outcomes (Section E). For a child with SMS, this often requires a combination of direct specialist input, trained staff support, and consistent strategies embedded across the school day.

An example of detailed provision might include:

A therapy programme designed and overseen by the Speech and Language Therapist, implemented daily by trained school staff. This will include modelling and supporting the use of agreed functional communication tools throughout lessons, transitions, and structured play activities.

Further details of how this support is delivered might include:

- Staff Training: Staff (ideally named) working directly with the child will receive training from the Speech and Language Therapist in functional communication approaches, speech sound support strategies, and the consistent use of visual and non-verbal communication supports. Training will be refreshed annually and following any significant change in need.

- Classroom Support: Support from a specialist teaching assistant with relevant training, available across all lessons to scaffold communication, support engagement, and reinforce communication strategies consistently.

- Generalisation Across Settings: Structured opportunities for the child to practise communication skills beyond the classroom, including during playtimes, transitions, and group activities. This will include staff-led structured playground games involving peers, designed to encourage interaction and communication in a supported way.

- Review and Adaptation: Provision will be reviewed regularly through ongoing monitoring and at annual review meetings. If progress is slower than expected, strategies and levels of support will be adapted in line with professional advice and evidence of what is most effective for the child.

This level of detail ensures that provision is clear, legally enforceable, and deliverable, while also allowing flexibility to adapt as the child develops.

Linking Provision to Training and Delivery

Many elements of effective provision rely on the skills and confidence of the adults delivering it. How staff are trained, how strategies are embedded across the day, and how specialist advice is translated into everyday practice can have a significant impact on outcomes.

This is explored in more detail in our article, Delivery of EHCP Provision for Children with SMS, which looks specifically at the role of staff training, therapeutic models of support, and how provision can be delivered consistently and meaningfully in real school settings.

Conclusion

An EHCP is most effective when there is a clear and logical connection between a child’s needs (Section B), the progress they are expected to make (Section E), and the support put in place to help them achieve those outcomes (Section F). This “golden thread” is particularly important for children with complex and evolving needs, such as those associated with SMS.

Clear, specific, and evidence-based writing reduces confusion, supports collaboration between families and professionals, and helps ensure that support is delivered as intended. Keeping plans up to date, reviewing provision honestly, and adapting support as a child grows are all essential to maintaining an EHCP as a live and meaningful document.

While future reforms to the SEND system may bring change, the principles of good EHCP practice remain the same: clarity, consistency, collaboration, and a shared focus on helping each child reach their full potential.

How the Access Card can Help People With SMS

How the Access Card can Help People With SMS